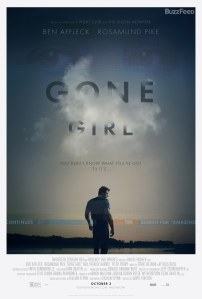

A Tale of Two Books: Outlander and Gone Girl

I have been thinking and talking a lot about adaptation over the past few weeks. Between Outlander and Gone Girl there is a lot to be talked and thought about. About what works, what doesn’t, who gets to stay, who has to go, and how to tell the same story maximizing the strengths of different mediums. My friend Maggie and I did weekly debriefs after every episode of Outlander and I won’t admit to how many text messages have been exchanged on the subject, but if this were Card Sharks I would recommend you say “I’m going to have to go higher than that,” to the number that originally popped in your head. (Read Maggie’s post about Outlander here if you’re interested.)

It is probably important to say right up front that I loved Gone Girl when I read it last summer and I only read Outlander in preparation just before and right after the series premiere. I have only read the one book. (I did start, but didn’t finish, the second one. There are eight books total.) While I have an ongoing love-affair and word-crush on Gillian Flynn’s wicked Nick and Amy Dunne, let’s just say that if my feelings about the Outlander universe were a Facebook status it would be “complicated” or just display the “Ask” button.

For Outlander, Ronald D. Moore, the amazing showrunner who brought Battlestar Galactica to TV, said in an interview with Variety that he always intended to do a very “faithful adaptation.” According to Moore, Chris Albrecht, the CEO of Starz, said, “make this show for the fans and trust that anyone who’s not a fan will be swept up in the story the same way all the readers were.” He has, for the most part, been true to his word, at least as much as a person who has only read the book once can tell. Also, it seems, Outlander book-fans are mostly pleased. Diana Gabaldon also seems,by a quick review of her posts in a CompuServe forum–the same CompuServe forum where she originally posted early drafts of the first novel, thrilled. (That’s not a typo. Yes, a CompuServe forum. Those still exist.) She even appeared in the show, with a speaking role, in “The Gathering” episode.

For Outlander, Ronald D. Moore, the amazing showrunner who brought Battlestar Galactica to TV, said in an interview with Variety that he always intended to do a very “faithful adaptation.” According to Moore, Chris Albrecht, the CEO of Starz, said, “make this show for the fans and trust that anyone who’s not a fan will be swept up in the story the same way all the readers were.” He has, for the most part, been true to his word, at least as much as a person who has only read the book once can tell. Also, it seems, Outlander book-fans are mostly pleased. Diana Gabaldon also seems,by a quick review of her posts in a CompuServe forum–the same CompuServe forum where she originally posted early drafts of the first novel, thrilled. (That’s not a typo. Yes, a CompuServe forum. Those still exist.) She even appeared in the show, with a speaking role, in “The Gathering” episode.

My question is how do people who hadn’t or haven’t read the books feel? Or how about someone, like me, who frankly didn’t like the book itself, but thinks the idea of a TV show with these characters could be compelling? In answer to the first, my friend who hasn’t read the book abandoned the show after three episodes citing too much voiceover (which is often text taken directly from the book) and a disjointed, muddled story. This is far from a scientific sample, but I don’t know anyone else who is watching on their own that hasn’t read the books.

In answer to the second question, I keep watching. And I watch closely. It’s become a project of sorts. I read articles and interviews. I listen to Outlander podcasts. (Including one called The Scot and the Sassenach, where the original premise is that she’s read the books and he hasn’t.) I do this for two reasons: 1) I’m interested in storytelling and craft and how that differs between books and television, and, 2) So many really smart people in my life LOVE these books and I’m convinced I must just be missing something.

My conclusion after a grand total of eight episodes is, well, I don’t know what. The television production is breathtakingly beautiful, well thought-out, and well constructed. It might as well be a Visit Scotland! promotional film for the Highlands. The costumes, set and art direction are phenomenal. The acting is real and compelling. The characters and settings are engaging. The story? Well, it’s…okay. It kind of moves along like the book that I didn’t very much care for. And it does that on purpose. And I’m bothered by that. But, I think, I might be the only one. No one else seems to care.

So, after this experiment of mine with Outlander, I did have some reservations going into the Gone Girl movie. The book is not a sprawling, multi-book epic with thousands of pages spanning time and generations, so it should be easier to adapt. But it was also a long, twisty book with a lot of time spent in the character’s heads, sort of like the first Outlander book. And, even though I am very clearly a Gillian Flynn fan (I HAVE actually read all of her books—there are three), it is complicated to adapt your own work. Thinking about all of the editing and revision that goes into a novel and then going back and doing another round. Well, that’s just hard on the brain.

I was in my seat on Saturday ready to love Gone Girl, but willing to admit I might just love it because of the book and Flynn. But I didn’t have to love it for anything other than the movie on the screen. It is weird and mysterious. Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor, who collaborated on the score, and David Fincher really seem to get each other. So, I starting thinking about why (discounting for my experience with the source material) this worked for me so much more than Outlander. I tried to “unpack my feelings” as Maggie would say and I also started digging around on the internet.

I was in my seat on Saturday ready to love Gone Girl, but willing to admit I might just love it because of the book and Flynn. But I didn’t have to love it for anything other than the movie on the screen. It is weird and mysterious. Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor, who collaborated on the score, and David Fincher really seem to get each other. So, I starting thinking about why (discounting for my experience with the source material) this worked for me so much more than Outlander. I tried to “unpack my feelings” as Maggie would say and I also started digging around on the internet.

Flynn said this, in Rolling Stone:

It boils down to the plot, which moves everything (and is very hard to disassemble too much) and making these characters believable so you can go to the crazy places that the story goes.

I kind of approached it…I was a writer for 10 years for a weekly magazine [Entertainment Weekly], and had spent so much of my time having my 1,000-word piece suddenly be a 200-word box, and having to disassemble it and create it as a new thing. I think that helped me be pragmatic about it; I sort of had a ruthless, “I killed my darlings” approach to it.

David Fincher commented on NPR that if everyone who had bought the book came to the movie and brought a plus one the movie would probably lose money. So the movie had to be a property that stood on its own, with or without the loyalty of the fans of the source material.

Those approaches show in the final product. They boiled the book down to its essential materials and then built it back up. And built it differently. And didn’t worry too much about the fans of the book.

Now, I recognize that movies are very different from TV. Flynn and Fincher just have to convince people to show up once. Moore and Outlander have to keep the audience coming back. Diana Gabaldon has, according to Google, sold over twenty-million books, so if a tenth of those people–and only those people–watch Starz on Saturday night, the show’s a hit. If the same percentage of Flynn’s readers go see the movie, that would be a major problem.

But, even so, in my (as previously stated–minority) opinion, the Outlander adaptation is at its best when it’s more like the Gone Girl adaptation–loyal to the source material but not beholden to it. Adaptation, in the context of movies and TV, strictly speaking, is the alteration of the source material to make it suitable for filming. In a basic, literal sense, doing what is necessary to make the book fit in a visual medium.

But adaptation has another meaning, the biology one, that says that adaptation is “a change or the process of change by which an organism or species becomes better suited to its environment.”

Outlander and Gone Girl are both successful adaptations, if success is judged by the definitions above. I would just argue that Flynn and Fincher’s adaptation is more organic, more primal, more evolutionary. This is a new species of Dunne.

That, to me, is much more interesting.