The Feminist Moment In “Groundhog Day” You Might Have Missed

The superhero scale of Wonder Woman’s feminism has been getting a lot of well-deserved praise. (Even a jiggle of Wonder Woman’s thigh inspired a body-positive Tumblr post about the male gaze that has gone viral.)

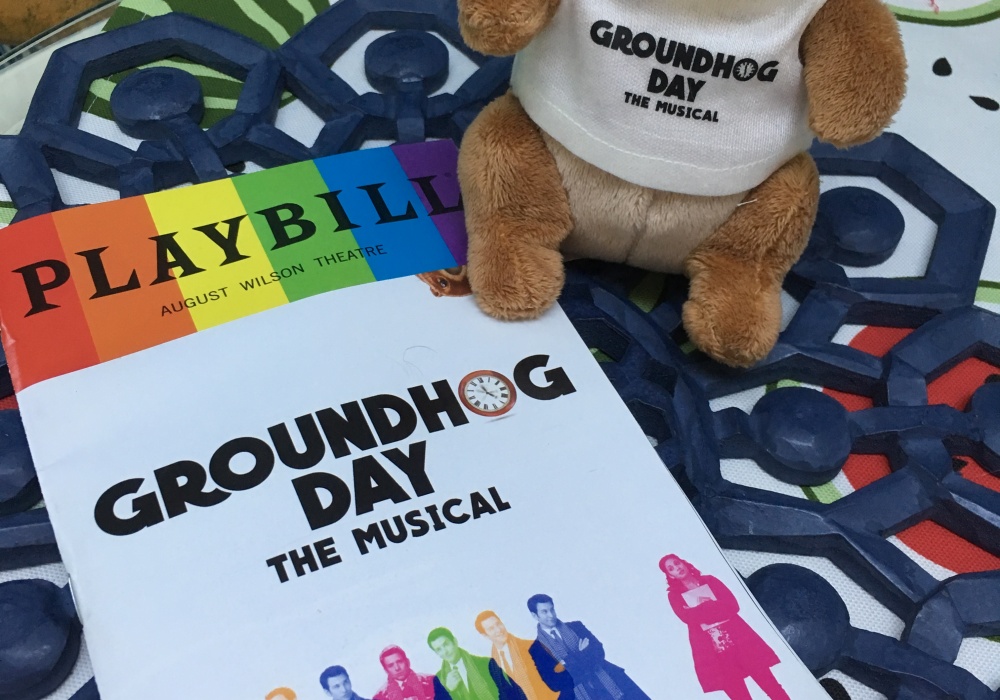

Sure, Wonder Woman’s feminist power pose is mighty, both literally in the form of Gal Gadot and figuratively in the impact she is having on audiences (and studio executives.) But there’s another character making a statement about women in movies. It’s happening live, eight times a week, at the August Wilson Theater on 52nd Street in Manhattan. Her name is Nancy.

Nancy steps alone into the spotlight at the opening of Act 2 of Groundhog Day: The Musical. The moment is both as unexpected as it is moving. Having trouble remembering her? Nancy Taylor is a minor character in the original 1993 movie. In the movie, Nancy shares an awkward one-night stand with Bill Murray’s Phil Connors. She only has a couple of minutes of screen time. She’s pretty. She’s fun. She’s a punchline. That’s all there is to the big screen Nancy. In the musical, she isn’t much more. That is, until that moment at the start of the second act.

Tim Minchin, composer and lyricist for Groundhog Day: The Musical, gives Nancy some redemption with that spotlight moment. “Playing Nancy” forces the audience not only to see Nancy but to listen to her. He uses the moment as a chance to improve on the original, a chance to look the Bechdel Test straight in the eye for a story that doesn’t. (Even so, both the movie and the musical come up short by Bechdel standards.)

Nancy challenges the audience to examine the role of women in film and in society. Minchin’s words speak for themselves: “I’ll play whatever role I’m cast in,” Rebecca Faulkenberry as Nancy sings. “If you look good in tight jeans, that’s what they’ll want you dressed in.” Then, finally: “Who am I to dream of better?/To dream that one day I’ll be something more than just collateral in someone else’s battle/I will be something more than Nancy.”

In a show filled with physical comedy and a score that gives an exaggerated wink to the pop motifs of the movie’s original music, “Playing Nancy” is a meta exercise in female empowerment.

Groundhog Day is a story about redefining yourself and grappling with the existential challenges we tackle every day, whether that day’s challenges are new or soul-crushingly familiar.

“Playing Nancy” is at once both off-putting and engaging. From a storytelling perspective, the song makes no sense. There is no narrative reason for the audience to get to know Nancy better and perhaps that’s why, in the original film, we never did. But, perhaps, the reasons of the original are more sinister, if unintended. Nancy is simply another obstacle in Phil Connors’ journey, less important than the ever-present alarm clock announcing 6:00 AM. Nancy isn’t a real person. She’s just one of the things Phil manipulates along the way. One of the brutal ironies of romantic comedy tropes is that there is only room for one happy ending and Groundhog Day reserves that for Rita, Phil’s producer and love interest, not Nancy.

For every Wonder Woman, there are a hundred Nancys, even now, but Minchin’s acknowledgment of this one Nancy is a powerful thing. As Minchin has said about the show, “It’s deeply profound in a very gentle way.”